During an April 2012 trip to County Cork, Ireland, I took a wild chance to find the illusive spot where my uncle was hung by the British in 1824. I was rewarded by an amazing revelation that unraveled a mystery that has haunted my family for generations. I am grateful to the many wonderful people who I met during that adventure, including the priest, undertaker, and town historian of the tiny town of Newmarket, County Cork, Ireland.

Captain Timothy (Tadgh) Cotter (about 1804-1824) — my 3rd great grand uncle was a Rockite commander and key leader of the Whiteboys in the early 1800s. He was from Mennygorman near Newmarket, Cork, Ireland.

His parents were John Cotter of Clonfert (-1812) and Catharine Murphy (-1832). Little is known about the lives of his parents.

His parents were John Cotter of Clonfert (-1812) and Catharine Murphy (-1832). Little is known about the lives of his parents.

Timothy lived and died during a time of much suffering in Ireland. The early 1820’s were marked by agrarian upheaval. The brutality of soldiers toward peasants, massive starvation, and excessive taxation by landlords led to revolt. The agrarian action against these conditions is known as the Whiteboy movement. Timothy became a key leader within the movement.

A description of the events leading to Timothy’s death is provided by Dan Cronin in his article “The Public Hanging in Ireland:”

On January 24, 1822, a group of Whiteboys seized a mail coach at Toonadrum and took the mail and pushed the coach over a cliff. Bands of soldiers were shortly on the scene and a fight ensued… Many Whiteboys were reported killed with no causalities to soldiers. Later that day when news reached Rathmore, panic set in because people knew reprisals would follow… When communication was severed, an ex-soldier named William Brereton came forward. He said that if he was well armed, well paid, and had a good escort that he would take the mail through to the English rulers. When Brereton began as courier, he traveled for hours but at one spot was challenged by a small body of Whiteboys. An argument developed and Brereton whipped his horse and brandished his gun through the leaderless and unarmed peasants. This happened again with another group later on. At the Parish Chapel, a band of Whiteboys accosted Bererton and his escort, calling for Brereton to surrender but he refused. Instead, he fought desperately to cut through but in the fight his horse was hamstrung and soon fell. At this point, Brereton was taken prisoner.

There were long discussions about Brereton’s fate. Appeals were made to save his life including by the priest. He had almost convinced his captures to set him free when word came through that the areas was surrounded by soldiers. Strangers also objected to setting him free. He was sentenced to be shot. He was allowed to make peace with God and then was executed. The crowds then dispersed and soldiers moved in to remove the body to Killarney.

For weeks afterwards, soldiers fine combed the area around Rathmore, brutally treating the aged, ill, women and children. Eventually, they arrested six men. A thorough search was made for the leader of the Whiteboy movement who was thought to be in the district. That leader was Timothy Cotter, a journeyman and blacksmith, and native of the Newmarket area. But he was well guarded and eluded the soldiers and slipped through.

Afterwards six men were arrested and five were found guilty and sentenced to death. They were executed in front of the jail before a large crowd on August 10, 1822.

All the while, Cotter, the “will o’ the wisp” roamed through Kerry, Cork, and Limerick. Other times he simply appeared in a district. Here, late at night he would address a meeting in some isolated farmhouse — there he would form another branch of the Whiteboys. By daybreak he would have moved on, at all time only hours ahead of his relentless pursuers.

During the night of June 7, he called to a house at a place near Newmarket and took a few hours sleep. Though the owners of the house tried to hide his identity, he was recognized by a maid-servant. She passed on the information and dipped his gun in a bucket of water. In a short time, the house was surrounded. Cotter jumped to his feet and went for his gun, only to find to his horror that it was “dead.” He ran to a window at the back of the house, and but for the same female he would have gone through. She threw a horse winkers and long reins beneath his feet which caused him to fall to the ground where he was overpowered. He was removed to the jail where he was tried for the murder of Brereton, found guilty and sentenced to death…

He was ordered to be executed on Monday August 15 at Shinnagh Cross — almost the same spot were Brereton was put to death. He was escorted from Traloe to the place of execution by horse and foot police and two companies of infantry. A Father O’Mahoney from Traloe remained with him up to the moment of his execution — it took place about 2:45pm.

On the night prior to the execution a mobilization of all the able-bodied men of the East Kerry area took place. They were hoping Cotter might be rescued — a vain hope. On the morning of the execution, upwards of 600 men assembled on the Rathmore-Killarney Coach Road. But the authorities were again forewarned and their escort was made overwhelmingly strong. The rescue fell through and the poorly equipped peasants scattered as Cotter arrived in chains. Many people were brutally beaten by soldiers, though nobody was killed. But men were clubbed senseless, left and right.

The execution took place in a saw pit, at the turn just south of the Cross. There were immense crowds present and all the arrangements were carried out without a hitch — it took 45 minutes to erect the drop. During this time, Timothy Cotter remained in prayer. When at last the order was given, he walked firmly to the gallows. Turning he asked all present to pray for him — the drop fell and he was launched into eternity without a struggle. All present fell on their knees and men and women wept openly. Four or five members of his family were present at the execution. The body was placed in a coffin and again taken to Traloe to be dissected, as was ordered in his sentence. On the way to Traloe, a row broke out in Killarney where a mob tried to take the body off the military who were stoned. Several people were arrested and taken to Traloe Jail as the attackers were beaten off. Tradition tells us that the body was afterwards returned to his family and that the remains were laid to rest in the family plot, in Drishane, Millstreet, Co. Cork. This was the last public hanging in Ireland.

Under the control of the Crown, the English newspaper of the time The Connaught Journal of Galway (Aug. 23, 1824) attempted to twist the events of the hanging claiming that Captain Timothy Cotter “a wretched convict” was apologetic for his actions. As for the 600 people who came in support of Timothy and his beliefs, the The Connaught Journal twisted events to read “the immense multitude fell simultaneously upon their knees, and offered up their prayers to the throne of God, for mercy upon the misguided man.”

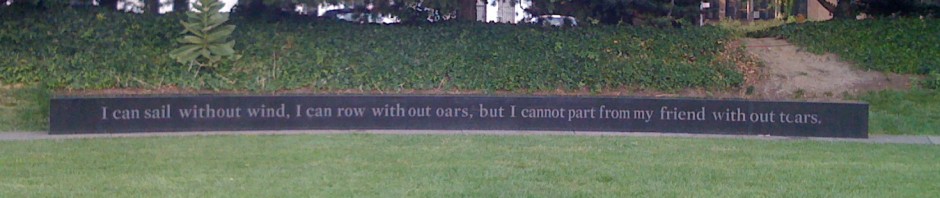

A marker can be found in Rathmore, Co. Kerry commemorating Timothy’s honor. It is engraved in Gaelic, probably to be elude the English before Ireland’s independence 100 years later. Against all odds and explanations, my husband Richard and I discovered the marker the first day we set out to unravel the family mystery of why Timothy was hung two centuries ago.

Located in Rathmore, Co. Kerry, Ireland with translation:

In Memory of

Michael O Foglu [Foley]

Matthew O Sullivan

Tadj O Healuite [Healy]

Liam O Healuite Healy

Art O Laoire [O’Leary]

Who finished their lives on 10th August 1822

In prison Craig-li

Tadg Mac Oitir (Cotter)

Who finished his life on 15th August 1824

At this place

These five were the

“Whiteboys” Who were put to death by the forces of England (Gall) in this country in their search

For the fight of freedom.

Timothy Cotter was a Rockite commander. The book “Captain Rock: The Irish Agrarian Rebellion 1821-1824, Part 66” provides context for Timothy’s activities:

As in certain earlier agrarian movement, there was a tendency for persons of elevated social status (yet well below the rank of gentleman) to be recognized as leaders of Rockite bands who members were drawn from different layers of society… Another revealing indication of the somewhat elevated social status of many Rockite leaders was their connection in some cases with members for the landed elite.

Cornelius Murphy, alias Captain Starlight, a principal in the attack on Newmarket during the insurrection of January 1822 and “well known in Duhallow as a notorious Whiteboy leader,” took the oath of allegiance to the king — a possible protection against arrest — from the magistrate Jeremiah McCartie on the day after the attack. McCartie, it was said, could not have been ignorant of Murphy’s character, since a local priest had earlier denounced him before McCartie as “the ringleader of all disturbances” in the the district. Timothy Cotter, even more famous as a Rockite commander in northwest Cork during and after the insurrection, long escaped apprehension; he did so at least partly because of the benevolence or restraint of more than one local magistrate. An irate and sarcastic Kanturk gentleman complained in 1824, shortly before Cotter’s capture: “In a letter to Judge Torrens last assizes I mentioned that to the disgrace of our authorities, Cotter was know to remain at ease with a few miles of this town, and had spent last Patrick’s day coursing with the eldest son of one our active magistrates.” …

Timothy Cotter, another chief Rockite of Duhallow barony, who was eventually executed for the murder of the mail-coach agent William Brereton in January 1822, was long able to avoid through the apparent connivance of certain magistrates.

It had long been official practice to arrange the public execution of Whiteboy offenders in such a way as to attract and impress large crowds of onlookers. This was of course done in the prosaic hope that the “awful spectacle” would drive home the lesson that serious agrarian crime frequently brought those guilty of it to a tragic but just end on the scaffold…”Immense crowds” were also attracted to the execution of Timothy Cotter in August 1824 when he was hanged at Shinnagh, the scene of the crime, for the slaying of the mail-coach agent William Brereton.

Less than 200 years ago, this public execution occurred in the presence of Timothy’s family while onlookers fell to their knees in grief.

If the psychological/spiritual “work” that we each need to try to accomplish involves making meaning of our life in the context of the flow of time, then what impact does this event have on the individual and collective psyches of Timothy’s descendants? Is meaning found in any attempt to lessen the suffering of others and in standing up to injustice? The shadow side — the disavowed part of ourselves — would be wondering about our own capacity for aggression as a means to an end.

I was drawn to Timothy’s hometown where I met two locals who were interested in sharing with me the location of two memorial stones that include his name. It was a first step in more deeply making sense of the the context of Timothy’s life.

Timothy lost his father when only a young boy. Perhaps his father — like son — was a Cotter Whiteboy. Timothy never married but his mother and siblings lived with his memory. His mother died eight years after her son’s execution. Timothy’s brother William Cotter married Mary Sullivan and had children who became comfortable in their lives as local farmers. One daughter Ann Cotter immigrated to the United States and married Daniel Sullivan and went on to live an affluent and notable life . Timothy’s sister Catherine Cotter married Jeremiah Quinlan and had five children with a few who immigrated to the United States.

William Cotter erected a memorial in honor of his parents and brother. Next to Timothy’s name are the words “for Erin” which translates to “for Ireland.”

Timothy Cotter died for freedom against oppression and is known to be buried in Drishane, Millstreet. Rest in peace great-great-great grand uncle. Not to be forgotten.

References

Daniel O’Connell & the Whiteboys

Journal of Sliabh Luachra No.1 — The Last Public Hanging in Ireland by Dan Cronin

Agrarian disturbance in West Cork 1822 by Ann Murphy, Terelton, Co. Cork

Suzanne:

Lots of echoes with Bat Shea! Was Cotter in the John Norton line of your family? What a fantastic story and well told. Eerie how you found the marker straight off. Thank you for letting me know about this and I look forward to more posts!

JACK CASEY

I share your family history ! Glad you enjoyed the trip to Cork. I live in County Clare.

My grand-mother was Norah Cotter, born in Meenygorman.

I knew most of the facts already, it was interesting to see them put together so clearly.

Best wishes Suzanne from Valerie Hamilton ( Johnson ).

Hi – I am Val’s sister Pam. I live in Liverpool but am over in Ireland for the weekend for Val’s granddaughter’s christening.

I knew a lot of the facts but as Val said it’s good to have them all there to refer to.

Pingback: William Cotter | Descent By SeaDescent By Sea

Hello. I am a descendant of Catherine and Jeremiah Cotter. I, too, have seen the monument regarding Timothy Cotter, back in 2001. I had heard afterwards, that the monument may be moved due to development. I’m not sure if that occurred, and based on the Connaught Journal article you reference, the location of his hanging was at the Cross of Sinnagh, nine miles from Killarney.

I am ecstatic to have found your website! Thank you!

Kay Quinlan

My name is Mike Kelleher and my mom was an O’Leary. Art who was also hung at Rathmore was born in the same house as I was near Barraduff on the way to Killarney.

Very interesting. More facts that we had. I am a descendant of Catherine Cotter who married Jeremiah Quinlan. They would be my great great grandparents. I only found the three children Catherine, William and Timothy. Do you know of more siblings? We could not find where Catherine and Jeremiah were buried. The person who posted the story must be a descendant of William Cotter?

Thank you for your interest. I don’t have any more information than what I have posted. Wishing you much success as you continue your search. Yes, I am a descendant of William Cotter.

Stumbled on your grand story researching ‘Rockites’ who came to Australia aboard Mangles (2) 8/11/1822, Celebrating that occasion & to pay trbute to the enormous contribution those men made to Australia over so many generations now.

Loved “The Last Public Hanging in Ireland” by the late dan Cronin, true friend and historian. Also acknowledge their contribution to Irish independence and well being.

Would appreciate a private personal contact:-

Brian Cronin >bscronin@hotmail.com 0408 230637